Introduction

Almost everyone can recount their COVID hobby. Whether it was baking homemade sourdough bread or binge-watching Tiger King, we all had a moment where we collectively did something outside the normal realm of everyday life, since COVID had all but destroyed the concept of “everyday.” I, too, initiated a hobby during my own COVID experience in 2022, one that ballooned into a three-year odyssey with the works of a single author, something I had never attempted before.

That fall, I was sick with COVID and killing time while recuperating. I decided to watch the documentary, United States of Amnesia, about the novelist, essayist, playwright, and all-around public intellectual, Gore Vidal (1925-2012). Describing himself as “America’s biographer,” Vidal was the foremost expositor and critic of the American empire, who keenly understood the United States’s complex and often contradictory history. Through his “Narratives of Empire” series of historical novels, Vidal reexamined central figures in the American story, such as Aaron Burr, Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. In the speculative fiction of novels such as Myra Breckinridge (1968) and Duluth (1983), Vidal explored the nature of time, the incompleteness of memory, and the chaotic experience of identity. As an essayist, Vidal was a prodigious critic of literature, a keen student of history, and all-around gadfly of the highest order on current events. In his later years, he became an acerbic critic of the Bush-Cheney regime and their criminal actions in Afghanistan and Iraq (this is where I first learned of him).

In my sick stupor, I decided that it would be fun and engaging to read every one of his books, to fully immerse myself in a single author. I would then write a short review of each book, which I would post with a picture of the title on Instagram. While I gave up posting them all on Instagram, I kept at the project—finishing all of his novels, collections of essays, and the majority of his published plays. I felt an intimacy with Vidal that I never encountered with an author before, approaching a vicarious reliving of his life through his work.

October 3, 2025 marked the centennial of Gore Vidal’s birth, the perfect time to bring my project to a close. What you’ll read over the next few blog posts are all the short reviews I wrote, in chronological order of publication (for the most part). Not included in these reviews are works I was unable to find online or in physical form, such as his plays “Weekend” and “A March to the Sea.” I also didn’t include the book Vidal in Venice, as it was actually written by a ghostwriter and not a part of his official canon. Finally, I omitted some of the essay collections, as their contents were covered by his award-winning collection, United States: Essays, 1952-1992.

Outside of the above works, I’ve read everything. And I’ve come to the conclusion that Gore Vidal is, without question or reservation, my favorite author. His interests are my interests (politics, literature, philosophy, history), his politics are largely my politics (a liberal or libertarian socialism), and his writing is what I aspire to as a wordsmith.

Early Years (1946-1954)

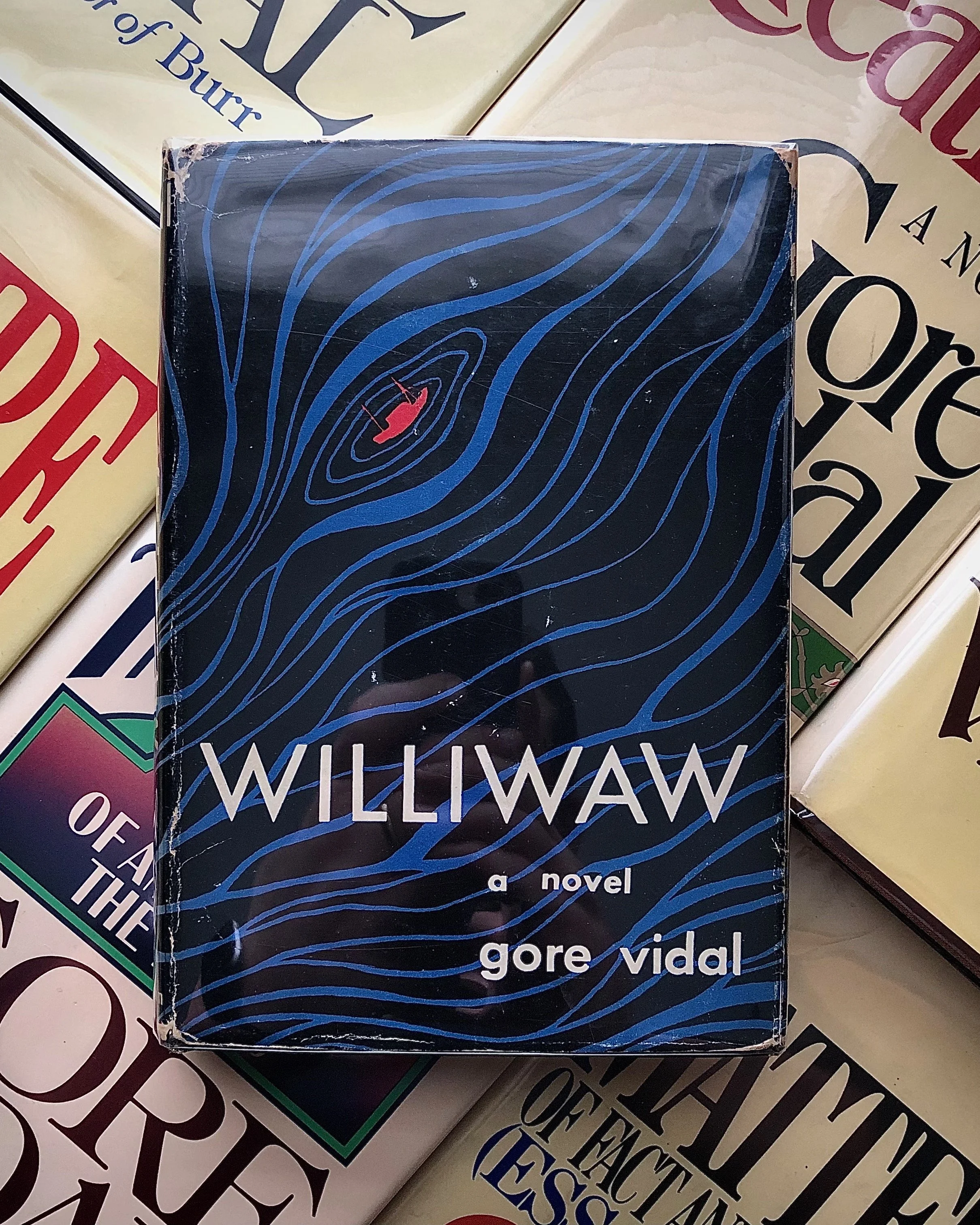

Williwaw, Gore Vidal’s first novel. He wrote it at the age of 19 while serving in the Army during World War II. Photo by the author.

Williwaw (1946) is Gore Vidal’s first novel, written when he was 19 years old and while serving in the US Army during World War II. It is a harrowing tale of survival, isolation, and desperation among the crew of a US Army ship on the treacherous waters of Alaska’s Aleutian Islands. Their charge is to transport an Army Major, a Chaplain, and other crew members from one island to another, all the while trying to avoid horrible storms on the high seas, known as “williwaws.” Vidal’s cast of characters in this novel are truly an ensemble; no one character is the center of the action: there’s the captain, Evans; his first officer, Bervick; Duval the engineer; Smitty the cook; and others. Tensions are high among the crew, as they are tired of war, isolated from family, and exhausted from bearing Alaska’s intense weather. Unfortunately for the crew, they encounter many storms that nearly destroy the ship and bury its crew in the deep. The most shocking scene comes towards the end, when Bervick, whose jealousy and dislike of Duval leads to the former murdering the latter and throwing him overboard. Captain Evans, anxious to get home and his crew away from intense investigations, convinces the military brass that it was an accident, despite his own knowledge to the contrary.

Williwaw is written in a direct, almost stark style, which Vidal attributed to his study of novelist Stephen Crane, whose Civil War novel, The Red Badge of Courage, is a classic in its own right. There are also shades of Joseph Conrad, especially with the book’s pessimistic tone. Despite its short length and sparse descriptions, the world Vidal creates feels very realistic and lived in; his characters feel like real people encountering almost insurmountable odds. Vidal also has a keen ear for dialogue, and when the novel focuses on the interactions of the crew and their thoughts on life, it really shines. He would write more elaborate work later in his career, but this first novel shows Gore Vidal at his most raw, a developing talent that in a few years would rock the literary world. For casual readers, it may be skippable, but for Gore Vidal die-hards like myself, it is an essential work.

In a Yellow Wood (1947), his second outing as a novelist, appeared more in the personal vein of later works like The Season of Comfort (1949) and The Judgement of Paris (1952). Robert Holton, a WWII veteran, has returned to civilian life in New York City as a financial analyst for a big firm. He’s trying to live the conventional life, but his past continues to interrupt his present. He runs into a war colleague who he has trouble reconnecting with and a past lover from Italy who he deeply cares for but is unable to commit to. He’s a man at a crossroads, and he chooses the path of least resistance in the end, trying to conform in an age of oppressive conformity.

Much like some of his early work, this is a novel where Vidal is finding his style as a writer, with all the limitations therein. I think his novels are better when they tackle bigger issues of philosophy, religion, history, and politics. The novel doesn’t really address any major themes, beyond having to choose between the past and the present, and I found myself a little bored at times with the writing. Its prose is rather utilitarian, similar to Williwaw (1946), but it doesn’t have the narrative thrust that novel had. My favorite part of the novel is Holton’s interactions with a diner waitress, and I hoped that maybe they would form a more meaningful connection as the story progressed, but alas, that didn’t happen. This is a read for Vidal enthusiasts only, but for the general reader interested in learning about his work, his later, more substantive novels are better fare.

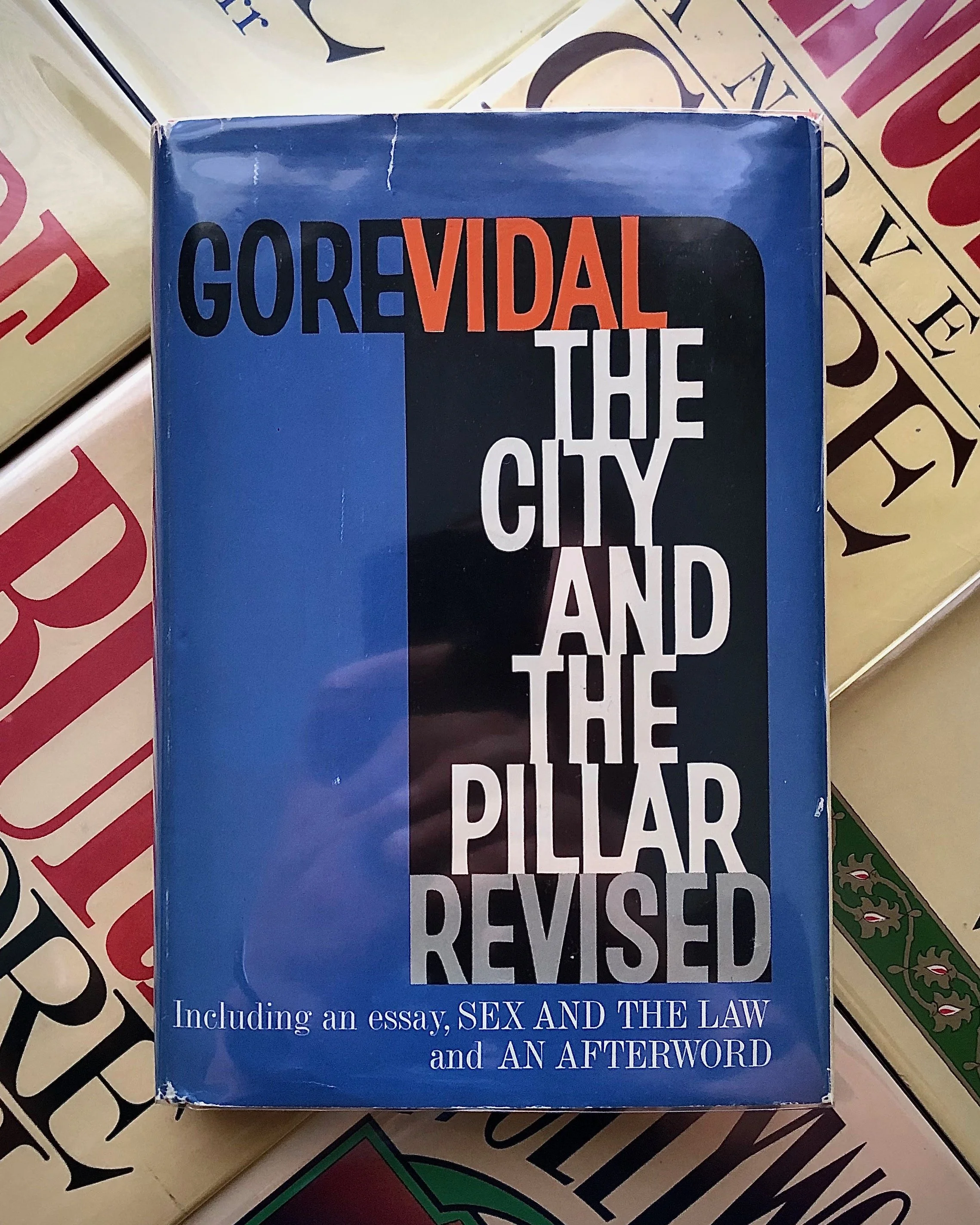

Vidal’s career, both as a writer and as a prospective politician, would be changed forever with the publication of The City and the Pillar. Photo by the author.

His career, both as a writer and as a prospective politician, would be changed forever with the publication of The City and the Pillar (1948, Revised 1965). A watershed work in Gore Vidal’s early novels, he left his mark as one of the first novelists in America to write openly, and with great eloquence, on the subject of homosexuality. The bisexual Vidal, whose own sexuality was a source of constant discourse during his life, used this novel as a way to express his own inner conflicts about his predilection towards men. The novel centers around two high school friends turned young lovers, Jim Willard and Bob Ford. Once their childhood days are over, the two men find themselves drifting farther and farther apart, as they travel and work around the world. Jim, who loves Bob and wishes for them to live forever in the bliss of their connection, cannot handle the separation from Bob and drifts from lovers and friends for years. Bob, on the other hand, becomes a family man, marrying a high-school classmate and having a child. When the two reunite after so many years, Jim wishes to rekindle their romance, but Bob thoroughly rejects him. Jim reacts horribly to the rejection, violating Bob and all that their past represented.

The clean, tight prose of this novel is deeply engaging; I couldn’t put this book down and finished it in a fury of reading over three days. Vidal’s tale of love lost and then destroyed speaks to how being gay or bisexual in the 1940s made you a social outcast. The character of Jim Willard is a tragic figure, whose yearning for love while never receiving it makes him a sympathetic character, despite his horrific actions against Bob at the end of the novel. Vidal’s own biography plays a role in this novel, to an extent. The romance between Jim and Bob is based loosely on his relationship with a classmate named Jimmy Trimble, who died in World War II. Whether their relationship ever became sexual is a matter of debate, but Vidal deeply cared for Trimble and was heartbroken to hear of his death at Iwo Jima. In all, The City and the Pillar is one of Vidal’s most poignant and personal works, imbued with a quiet defiance against the social norms of its time while delivering penetrating insights in the world of homosexuality in the post-war era.

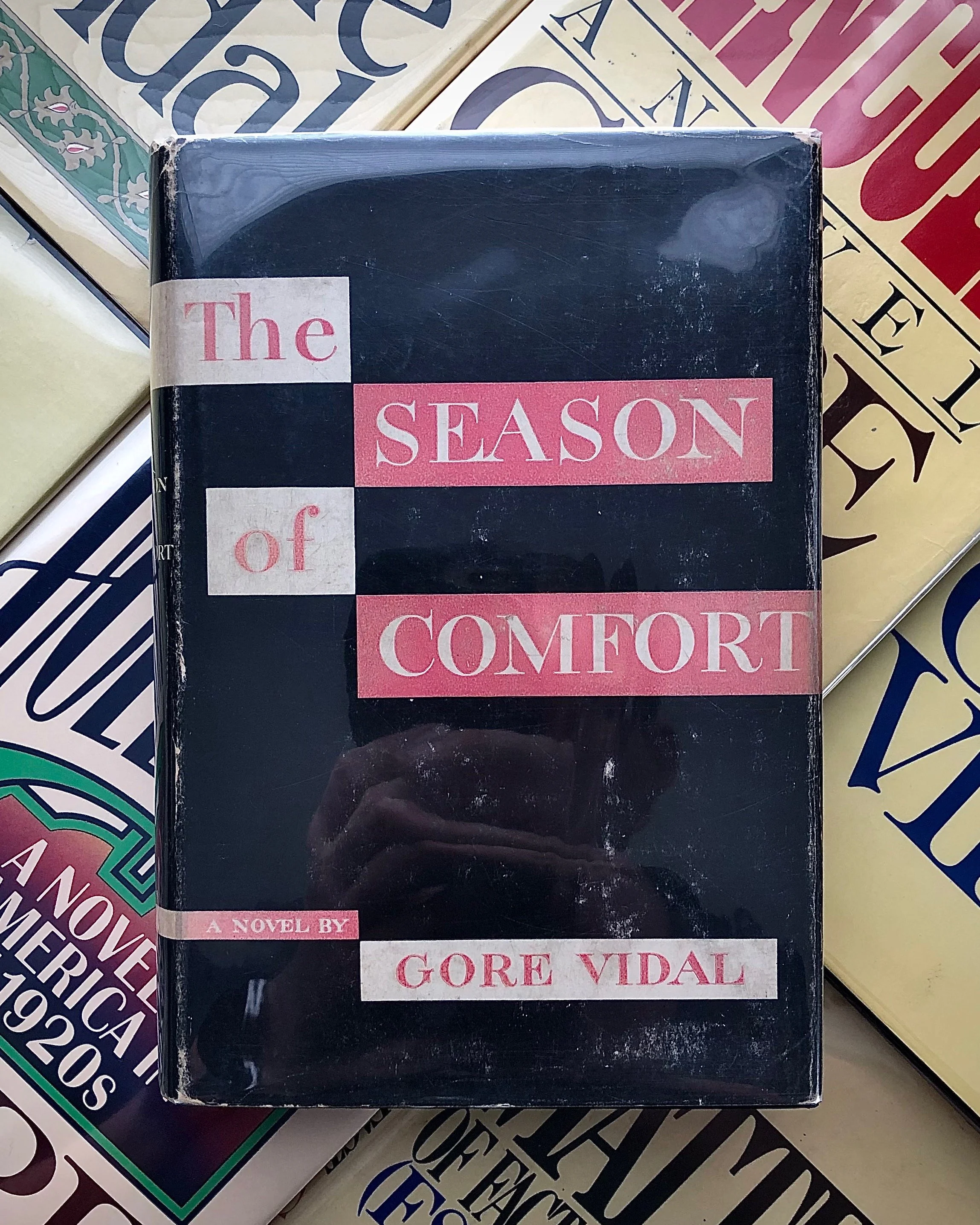

The Season of Comfort, Vidal’s semi-autobiographical novel about the dynamics of growing up in a dysfunctional family, is one of his lesser-known but important works. Photo by the author.

Vidal remarked once that his work was not autobiographical, but this is a misnomer. The Season of Comfort (1949) is such a semi-autobiographical work, of a young man’s upbringing with a tempestuous and overweening mother. Bill Giraud, the novel’s central character, is the grandson of a famous southern senator and the son of a painter turned diplomat. His mother, Charlotte, is the daughter of said senator whose own complicated relationship with her mother, Clara, informs her behavior with her son. Young Bill is a gifted child who loves to read and finds solace in the arms of his grandparents when his parents later divorce, either ignoring him (in the case of the father) or chastising him (in the case of the mother). We see Bill’s life move from home to boarding school, where he becomes friends with a young man named Jimmy, who holds a special meaning for him (a theme Vidal used originally in his 1948 novel, The City and the Pillar). Bill decides that painting is his calling and devotes his adolescence to honing his craft, despite his mother’s protestations. However, all of this is interrupted by the Second World War, and Bill enlists, gets wounded in battle, and will eventually return home at the war’s end, to resume his painting.

The novel’s structure is quite interesting, moving from first to third person, jumping from the present to the past, and contains an entire chapter called “The Parallel Construction,” where an argument between Bill and his mother plays out over separate pages for each character. This is the first novel of Vidal’s where he’s playing with form, narrative, and convention— something he would do to great effect in novels like Myra Breckinridge (1968) and Duluth (1983). I also identified with the story; as someone who grew up with divorced parents and a complicated relationship with his mother, I felt heaps of empathy for Bill and the struggles he went through. As the title suggests, seasons play a big part in the narrative, with winter seasons representing death and desolation and spring representing birth and renewal. While only in his early 20s when he wrote it, I think this novel is very mature, grounded, and thoughtful about the messy dynamics of a family. Of his early work, this novel is one of his best.

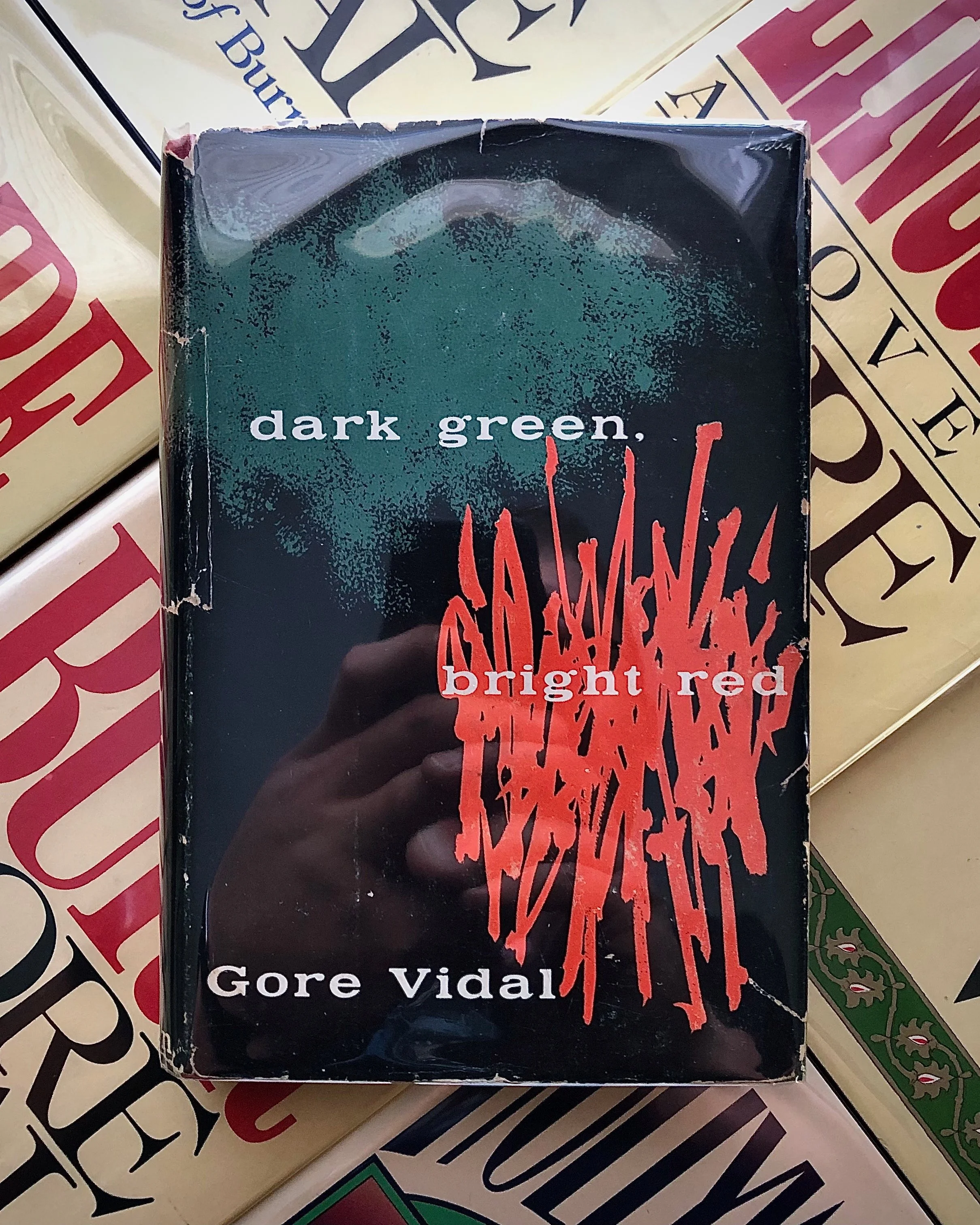

With Dark Green, Bright Red (1950), Vidal produced a solid attempt at a political thriller, with all of the intrigue, action, and romance that accompanies the genre. Photo by the author.

With Dark Green, Bright Red (1950), Vidal produced a solid attempt at a political thriller, with all of the intrigue, action, and romance that accompanies the genre. Taking place in some South American country (likely influenced by Vidal’s time in Guatemala during its decades-long civil war), the novel centers on the political machinations of General Alvarez, a strong-man dictator recently ousted from the country and who wishes to regain power. His leading advisor is Peter Nelson, a former US military man-turned-mercenary, who organizes a Bay-of-Pigs-style attack on the country in an attempt to return Alvarez to power. Peter falls in love with Alvarez’s daughter but knows their courtship is doomed by the deteriorating political situation. After the killing of Alvarez’s son and the failure to carry out a successful coup, it is discovered that one of Alvarez’s lieutenants orchestrated his own coup, which was backed by the largest company in the country. Peter flees the scene in time to avoid arrest and worse, never completing Alvarez’s coup and abandoning the one he loves.

While the novel’s action scenes are a bit tedious, it shines in its depiction of morally bankrupt and politically reactionary leaders whose only interest is gaining and maintaining an iron-grip on power. This is the first work of Vidal’s where he is grappling with the consequences of the American empire, how its own interests shape nations thousands of miles away, often to the detriment of their people. In real life, a coup against the democratically elected Arbenz government in Guatemala, instigated by the United Fruit Company and the CIA, would happen only a few years after Dark Green, Bright Red’s publication. One review described this novel as an “interesting failure,” and I think that’s a good way to sum it up. There’re a lot of compelling elements, especially in relation to notions of empire, but altogether it feels a bit stilted. Vidal would return to these themes with much greater effect in novels like Julian (1964) and Empire (1987). Overall, Dark Green, Bright Red is an attempt at a thriller that works better when it strays from the action and focuses on the politics.

A Search for the King (1950) could be described as Gore Vidal’s first “historical novel,” but it’s as much a legend as it is history. Set in the tumultuous 12th century, it’s the mythic tale of King Richard, his trusted troubadour, Blondel, and their exploits across medieval Europe and the middle east during the Crusades. Richard is kidnapped by rival monarchs, and the novel follows Blondel as he tries to find his King, interacting with many interesting people, places, and creatures along the way. Blondel encounters dragons, giants, menacing queens, and a young man named Karl, whose small-farm life leaves him desiring adventure and gallantry. Ultimately, King Richard, known as “Richard the Lionheart”, is set free and leads Blondel, Karl, and his army into battle against King John for control of England. Right at the end of the novel, we even meet Robin Hood, whose hatred of King John and desire for freedom in Nottingham leads to an alliance with King Richard. Richard’s army wins the day, but not without consequences; Karl, the young man whose thirst for adventure set him on a path with Blondel, dies in battle. It is with Karl’s death that Blondel realizes his own mortality and the sacrifices he’s made in his life in service to his king.

This is the first novel I’ve read of Vidal’s that I felt was just passable. Its prose is fine, even brilliant in some spots, but it doesn’t have the same passion or wit as some of his early novels, like The City and the Pillar (1948) and Messiah (1954). It reads more like something he wrote because he thought it would sell well, which made sense considering the critical and cultural backlash he received for The City and the Pillar. Nevertheless, I found A Search for the King an enjoyable read, and if you’re a Gore Vidal die-hard, definitely check it out. Otherwise, skip it and check out his more iconic and substantive work.

In the early 1950s, Gore Vidal began writing pulp novels under various pen names, as his literary reputation took a hit after the publication of his controversial novel, The City and the Pillar (1948), one of the first mainstream American novels to openly discuss homosexuality. The first of these novels, A Star’s Progress (also published as Cry Shame!, 1950) he wrote under the female pseudonym Katherine Everard. It is a sensational work that includes many of Vidal’s hallmarks that would appear in his later fiction: homosexuality, the movie industry, and characters whose inner life is vastly different than their public life.

Graziella Serrano is the daughter of a lion tamer from Spain who dreams of becoming famous in her own right. Beautiful, mature for her age, and extremely ambitious, she becomes a dancer at a late-night club in New Orleans. Her family is distraught by her choices and threatens to end her budding career, so she runs away from home and lands in the arms of a nice older man named Jason Carter, whose love for her gives her a new life. With his help, she becomes Grace Carter, the bombshell actress in Hollywood whose stunning looks and solid performances make her a star.

But all is not well. She never loves Jason the way he loves her, and she longs to have a dashing man of her own. Grace attempts a romance with a co-star, but his proclivity towards men precludes their relationship going any further. Burned out and tired of the limelight, she vacations in Europe where she meets a prince and falls madly in love. Their whirlwind affair is cut violently short by the start of World War II, and she’s left all alone back in Hollywood.

This novel falls in middling territory for me— not bad, but also not substantive. Vidal would take many of the elements from A Star’s Progress and repurpose them in one of his most celebrated and accomplished works, Myra Breckinridge (1968). Clearly he knew that he was writing a rather throwaway pulp novel, but nevertheless provided moments of strong characterization and clever dialogue. While it’s not a must-read among his works, it’s still an engaging novel that shows him developing his strengths as a storyteller.

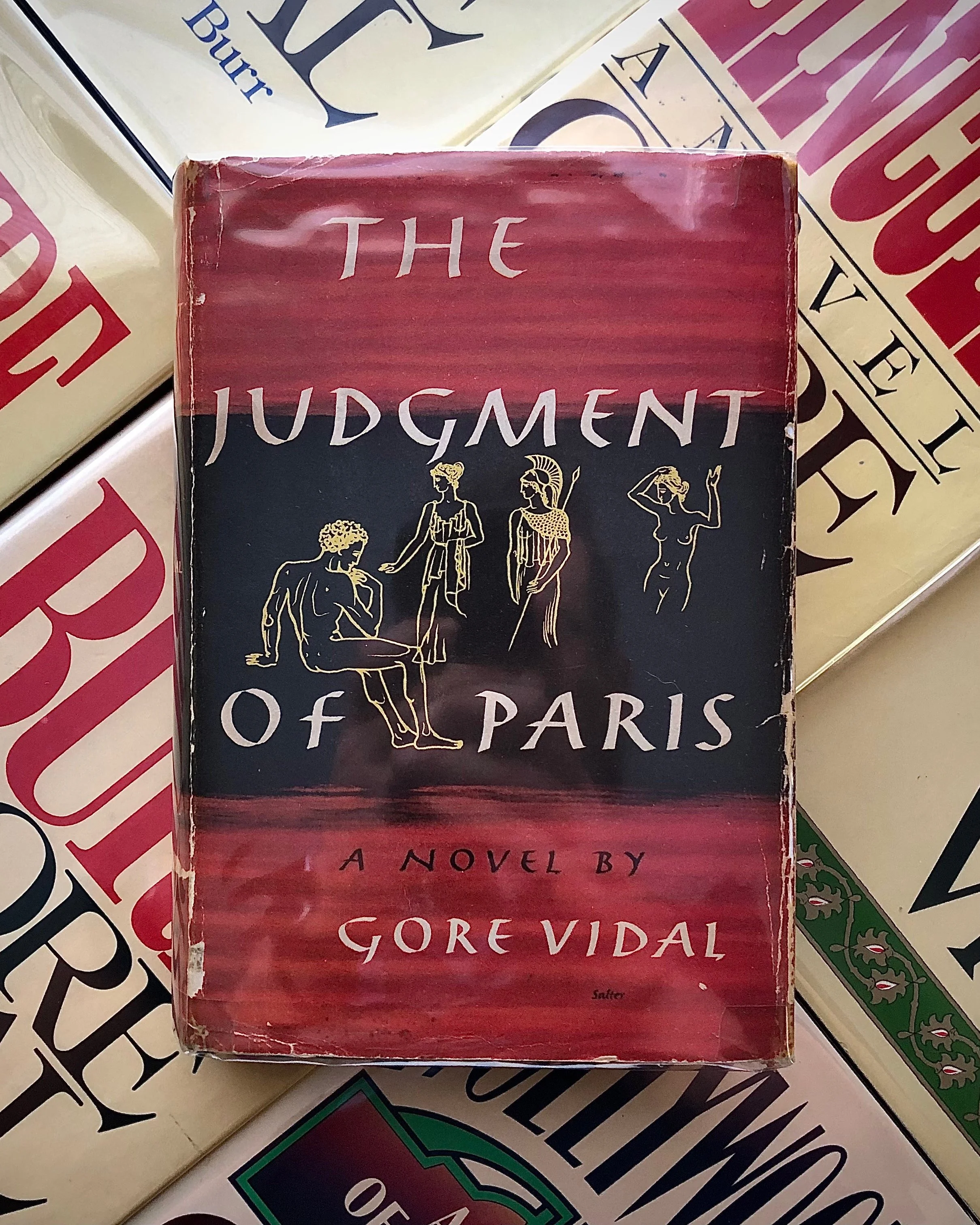

Vidal’s literary talent took a massive leap forward with The Judgment of Paris (1952), one of his most interesting, ambitious, and thematic novels. Photo by the author.

Vidal’s literary talent took a massive leap forward with The Judgment of Paris (1952), one of his most interesting, ambitious, and thematic novels. Philip Warren, a recent law-school grad who is taking a year to explore the world and discover himself. Through his interactions with three women, who represent power, knowledge, and love, respectively, he learns more about himself and what he truly wants out of his life. Along the way, he also encounters a zany cast of characters, from a Agatha-Christie rip-off novelist and a suicidal obese man to the head of a political cult and a debutante in search of a good time. All of these rich experiences show Warren the primacy of love and how its absence makes knowledge or power feel hollow.

On reflection, Vidal considered The Judgement of Paris the novel where he found his voice and style, and I agree. Gone are the clipped sentences of Williwaw (1946) and the straight-forward themes of In a Yellow Wood (1947); with Judgement, he lets his style breathe and his philosophical musings appear more pronounced. Like many of his later novels, he breaks the fourth wall with the reader and changes narrative perspective at times. Vidal is not afraid to move the reader in unexpected directions. The characters are lively, thoughtful, and often comically tragic, especially the character of Mr. Willys, whose own adipose tissue-addled existence provides the second act with its narrative thrust. Vidal is also grappling with the subject of religion in this novel, something he would address again in his masterwork, Messiah (1954). Vidal anticipates our secular age and how its own conceptions of the good life and the good society are often at odds with ancient creeds, and how this conflict will shape our lives— for better or worse. Of all of his novels, the Judgement of Paris is one of the essential volumes, full of wit, biting social commentary, and philosophical heft. It is a must-read in the corpus of his fiction.

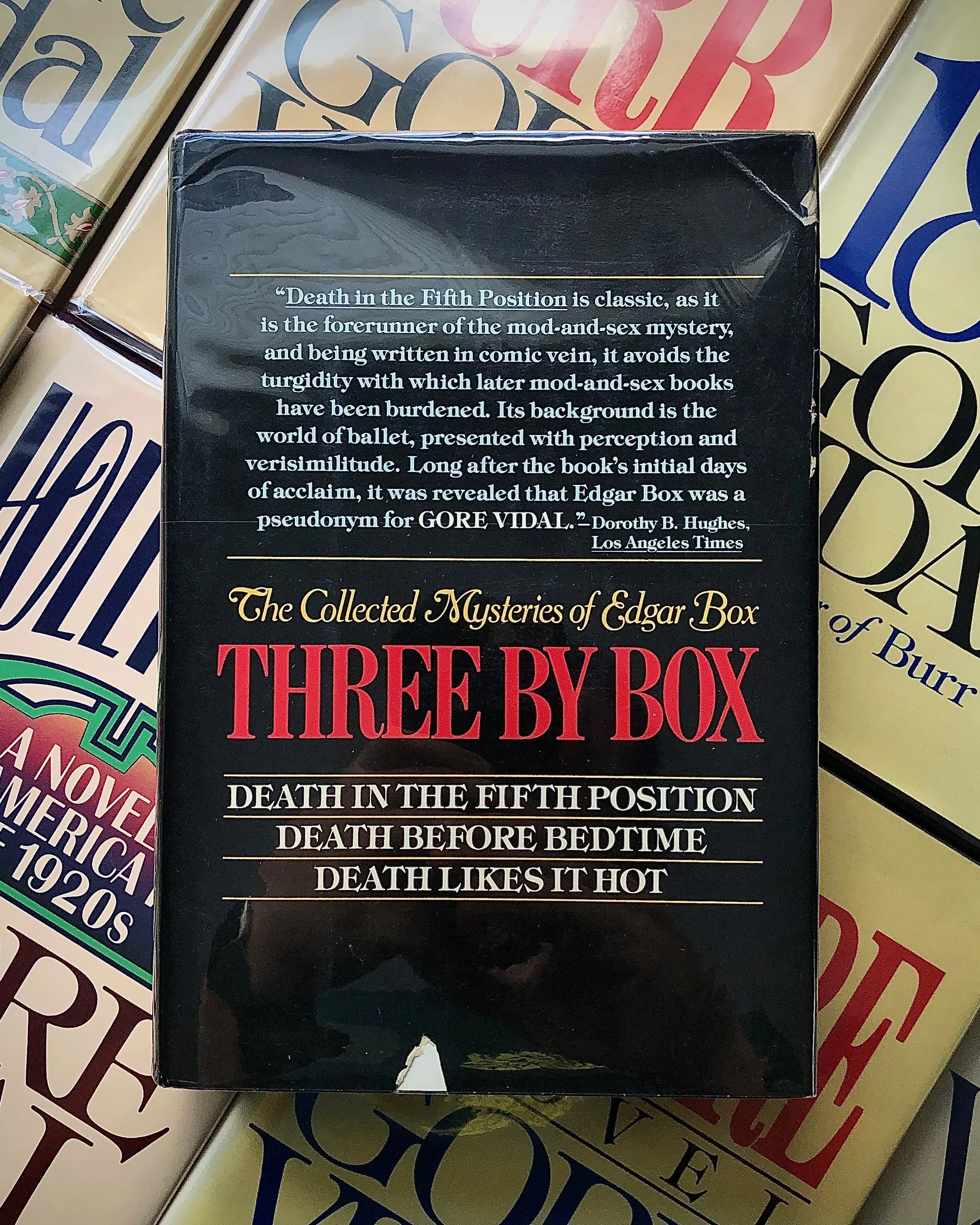

After the publication of The Judgment of Paris, Gore Vidal was in a place of career transition. His career as a novelist had cooled off since the publication of his pathbreaking, controversial novel on homosexuality, The City and the Pillar (1948). As such, the chief executive at Dutton, his publisher, suggested he write mystery novels under a pseudonym. Intrigued by the idea and having known many of the tropes of the genre as a reader of Agatha Christie, Vidal assumed the name “Edgar Box” (a combination of Edgar Wallace, the godfather of the modern mystery tale, and the last name of an acquaintance) and wrote three mystery novels in a short clip: Death in the Fifth Position (1952), Death Before Bedtime (1953), and Death Likes it Hot (1954).

Intrigued by the idea and having known many of the tropes of the genre as a reader of Agatha Christie, Vidal assumed the name “Edgar Box” (a combination of Edgar Wallace, the godfather of the modern mystery tale, and the last name of an acquaintance) and wrote three mystery novels in a short clip: Death in the Fifth Position (1952), Death Before Bedtime (1953), and Death Likes it Hot (1954). Photo by the author.

The main protagonist of all three novels is Peter Sargeant II, a dashing, witty public relations man and occasional journalist who finds himself stuck in the middle of mysterious murders with a colorful cast of potential subjects. In Death in the Fifth Position, he successfully solves the murder of a prominent ballerina whose star shined too bright to the liking of her killer. Death Before Bedtime, my personal favorite of the three, sees Sargeant exposing the murder of an ambitious U.S. Senator and prospective presidential candidate. In the final book in the trilogy, Death Likes it Hot, Sargeant unravels a fiendish murder plot in the Hamptons during the dog days of summer. All three have twists, turns, and red herrings—in the classic Christie mold—mixed with very clever dialogue and snapshots of American life in the early 1950s, albeit in power centers like New York and Washington, D.C. While certainly not among his best work, these three novels represent the strongest of Gore Vidal’s pseudonymous works and illustrate his singular knack for genre fiction.

Thieves Fall Out, another pulp novel that Vidal wrote under the pseudonym “Cameron Kay,” was originally published in 1953. It languished in paperback bins in used bookstores for years until its republication in 2015, three years after Vidal’s death.

The novel is in some respects the spiritual sequel to his novel set in South America, Dark Green, Bright Red (1950): a pot-boiling thriller with political undertones and muddled demarcations between hero or villain, at least on the surface. The novel is equal parts James Bond (curiously, Vidal’s creation came out the same year as Fleming’s first 007 novel, Casino Royale), Indiana Jones, and Sam Spade, with dashes of pulp adventure stories for flavor. Our hero is Peter Wells, a charming ex-soldier with a passion for travel, who finds himself in Egypt during the tumultuous final days of its king. Drugged and burgled out of his money, he finds work with a seedy network of underground smugglers, whose desire to sell a precious, historical necklace peaks his interest. He also falls in love with a German expat whose dark past makes it difficult to fully love him back.

Like many a paperback novel of the 1950s, there’s a lot of cheap stereotypes of foreign peoples, twists and twists of twists, and an all-American hero who always comes out on top. Yet, I never found these limitations a serious problem. As someone who grew up with James Bond and other mystery stories, I found the novel a familiar diversion that had hints of Vidal’s later literary glory. It’s not a must-read in his work, but an enlightening detour showcasing the development of his craft as a novelist.

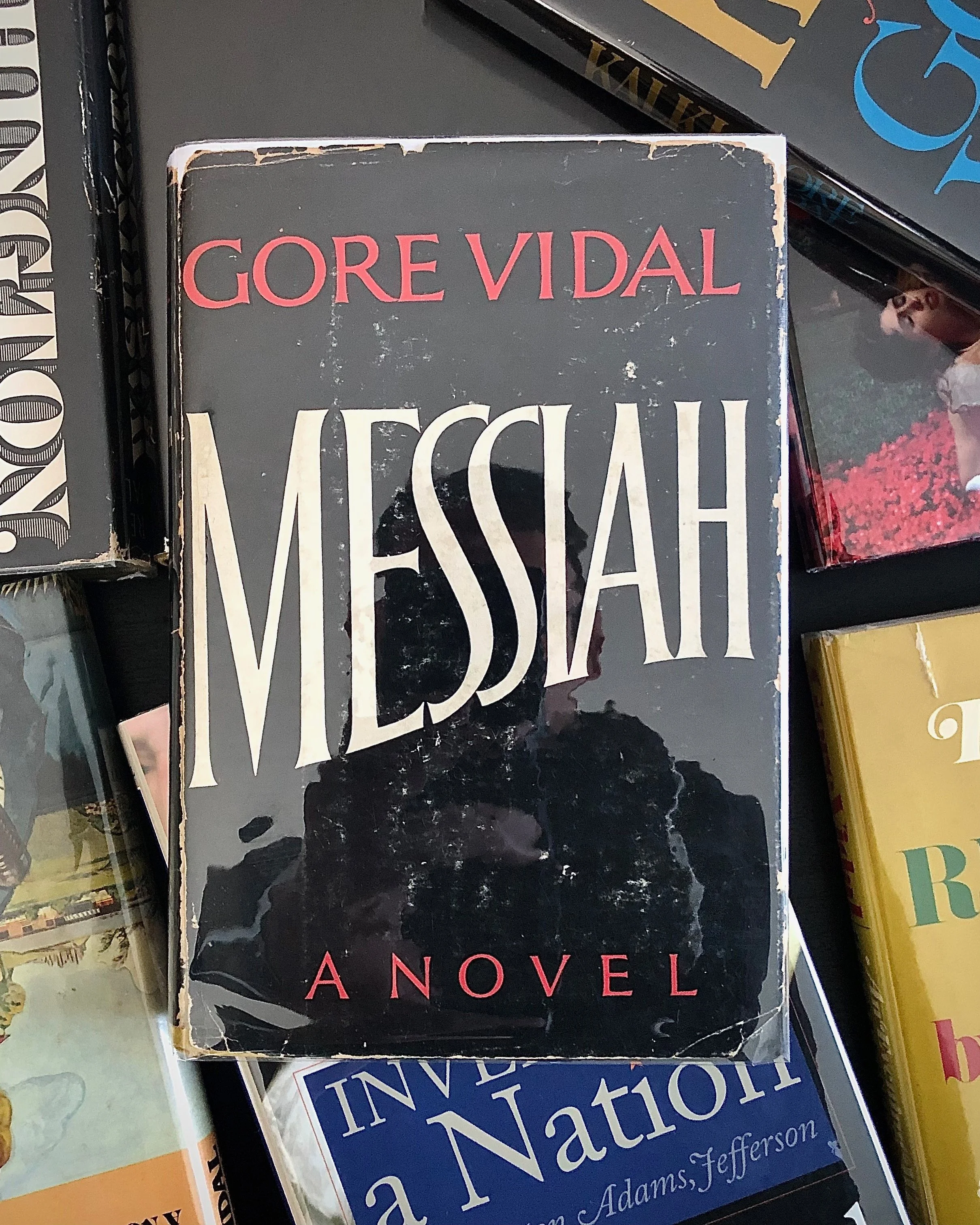

Vidal returned to writing under his own name with Messiah (1954), his finest novel on the subject of religion and easily one of his best early novels. Photo by the author.

He returned to writing under his own name with Messiah (1954), his finest novel on the subject of religion and easily one of his best early novels. Gore, ever the critic of religion in general and monotheism in particular, used the backdrop of the creation of a cult to explain his own secular humanism. The novel’s narrator is Eugene Luther (a semi-autobiographical name, as this is Gore’s given first and middle names), a contemplative man obsessed with history, philosophy, and theology. Originally poised to write the great book on the Roman emperor Julian, which Gore Vidal himself wrote a decade later, Eugene falls into a crowd of idiosyncratic spiritual seekers who congregate around a single, charismatic figure— the elusive John Cave. Cave, a sub-literate but deeply passionate man, envelops a group of followers who disseminate his teachings, called “Cavesword,” to the masses via paperback pamphlets and television appearances. Cave’s core belief is as follows: death is not a vile thing to be rejected, but a glorious return to the cosmos that we should embrace. Luther is tasked with writing much of Cave’s ideas down, either in the form of essays or dialogues, which further inculcate the public in Cave’s teachings. Luther’s own misgivings about the direction of the religion lead to clashes with other members of Cave’s inner circle, including Cave’s PR man Paul (apt name) and educational liaison Iris. It all culminates in Cavesword taking over the world, even eclipsing Christianity, at the cost of Luther’s humanity and Cave’s own life.

Messiah brilliantly illustrates how religions or cults are created, disseminated, accepted, and bifurcated. The novel perfectly captures how religion is an intense human affair, replete with cults of personality, interpersonal conflict, and arcane theological debates. In the end of the novel, Luther ultimately rejects the cult of death in the teachings of Cave and accepts the dignity and necessity of life. In essence, Vidal’s message in Messiah is one of profound humanism, which rejects the outmoded superstitions and traditions of the past while challenging the new superstitions that replace them. Messiah is a must-read novel from the voluminous canon of Gore Vidal.