Playwright and Essayist (1956-1963)

In the mid 1950s, Gore Vidal took a sabbatical from writing novels to try writing plays—specifically plays for television. At the time, television was an extremely new medium, with broadcasters green-lighting a wide swath of productions. In this milieu, live television plays became wildly popular, and Vidal wanted to get in on the action. His plays varied, from wholly original creations to adaptations of famous works.

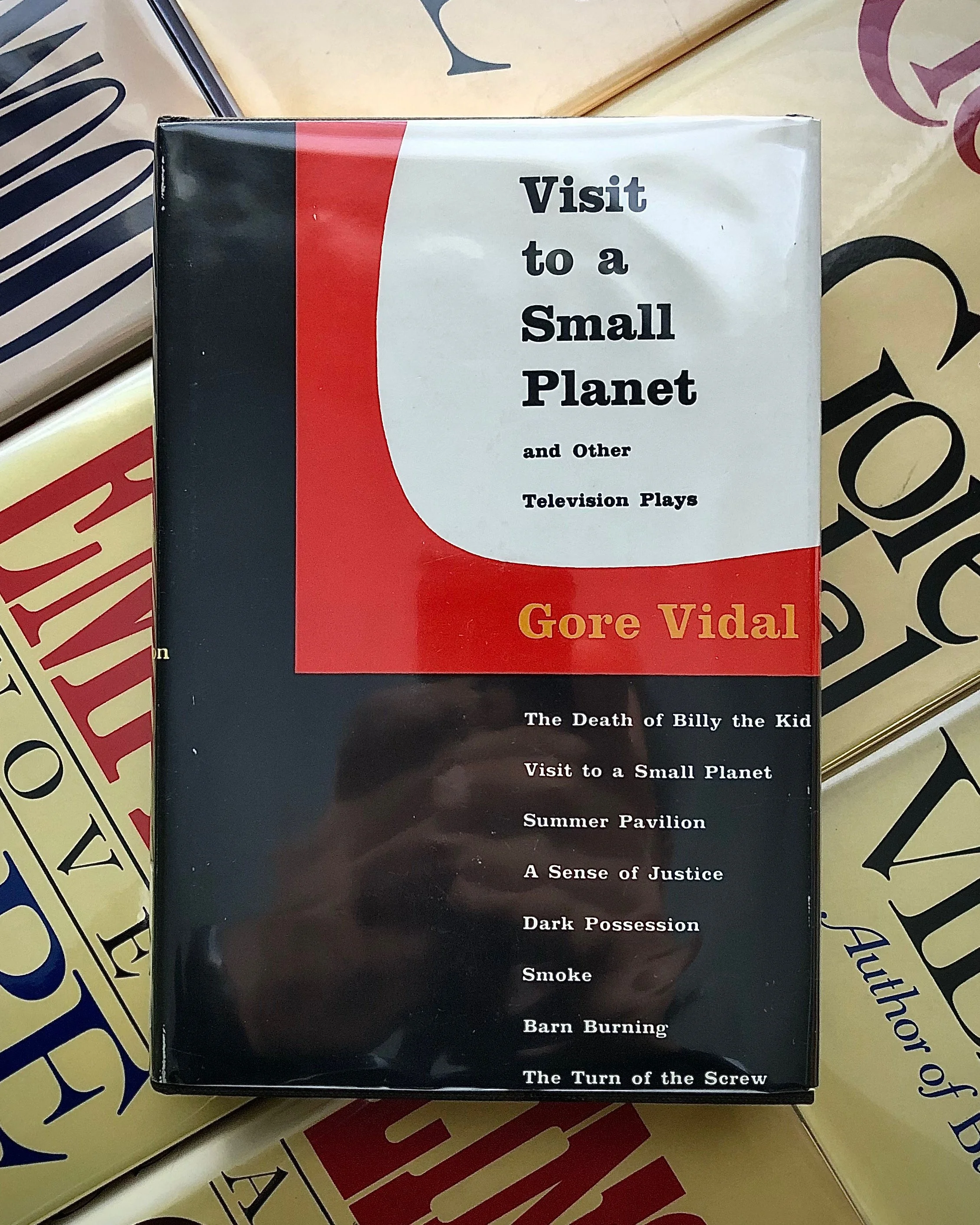

Visit to a Small Planet and Other Television Plays (1956) collects many of his best plays from that era and gives the reader a window into his days as a television writer. Some of the plays are classic, such as the haunting “Dark Possession” and the title play, a satirical farce on the follies of war. “Smoke” and “The Turn of the Screw” are plays based on stories from iconic American writers William Faulkner and Henry James, respectively, the latter of which was one of Vidal’s favorite writers and literary influences.

Visit to a Small Planet and Other Television Plays (1956) collects many of his best plays from that era and gives the reader a window into his days as a television writer. Photo by the author.

What is striking about these plays is the conditions in which they were written. In the introduction, Vidal explains how television worked in that era, with plays written at a frenetic pace, slapdash rehearsals, and a live broadcast which couldn’t be edited. This gave all the writers a sense of urgency and perfectionism, qualities Vidal had in spades as a young and ambitious writer.

A snapshot of one of the most interesting periods of Vidal’s career, Visit to a Small Planet and Other Television Plays displays a writer eager to hone his craft in a relatively new medium, largely with success.

He then expanded “Visit to a Small Planet,” into a full theatrical work in 1957, which opened on Broadway to great critical and commercial acclaim. A satirical play on the dangers of war and militarism, the setup comes straight from science fiction. An alien named Kreton (get it?) comes to earth in the hopes of witnessing the American Civil War, only to find out that he came 100 years too late, at the height of the nuclear age. While Kreton is disappointed to miss the war between the blue and the gray, he nevertheless enjoys his interactions with members of an American political family and a high-ranking general. Kreton goes to work developing an elaborate scheme to get the Soviet Union and the United States to go to nuclear war, as he’s bound and determined to see humanity destroy itself. Fortunately for us humans, he is thwarted in his attempt by others from his home world who then take him home. It is relayed to the Americans that Kreton is essentially a child, with immature desires who should never be left on his own.

This play is one of Vidal’s best, showing his talents for character, dark humor, and allegorical storytelling. Kreton, played by Cyril Richard in the original stage production, is a superb character to satirize the national security state and the constant march for war. In effect, he shows humanity the absurdity of nuclear brinkmanship and the costs of excessive military buildups. While some of the jokes are dated for today’s audiences, especially in their references to the Cold War, its overall message is timelier than ever. It’s a clear standout among his theatrical works.

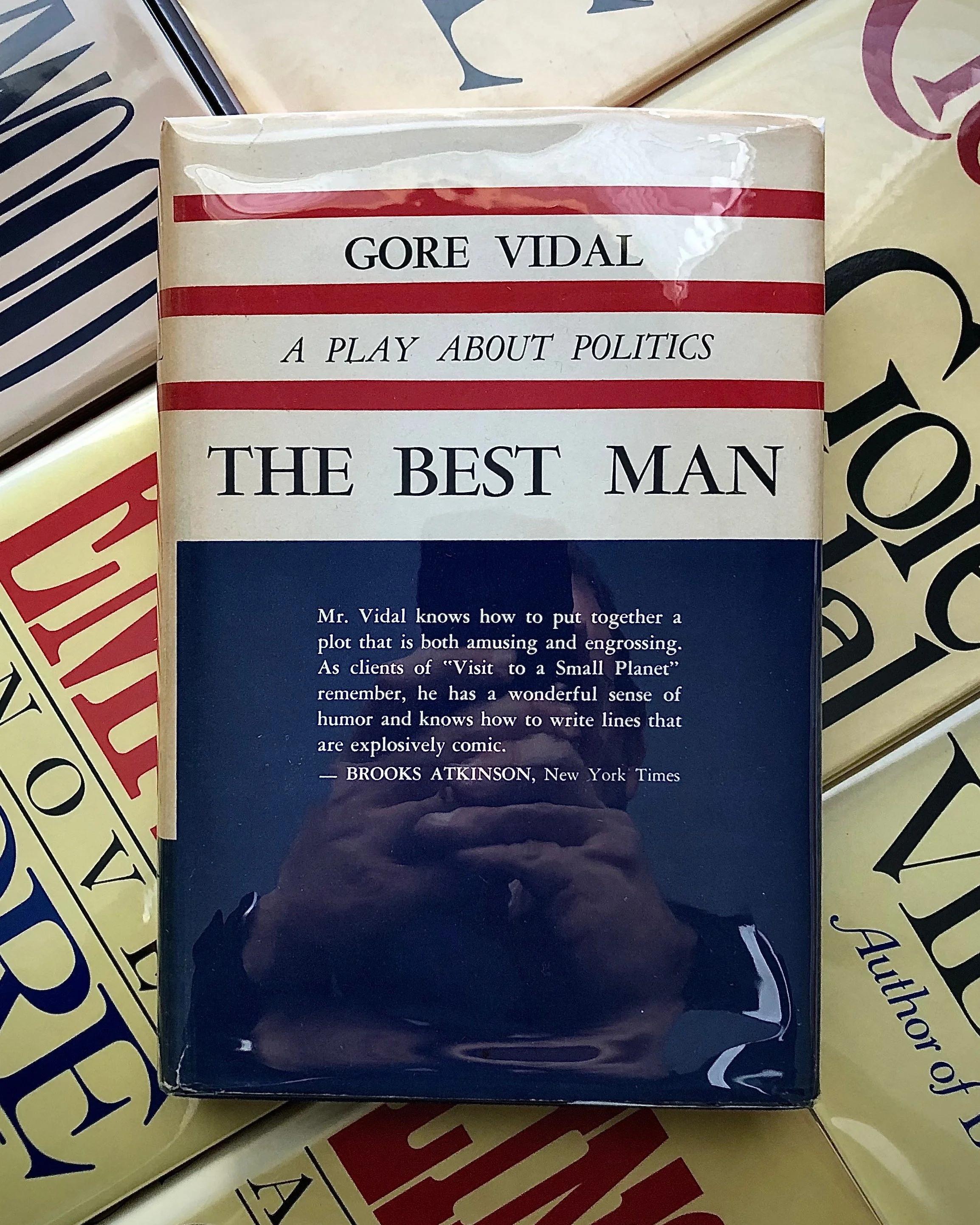

His talents as a playwright came to their apogee with The Best Man (1960), a timeless classic on the machinations of presidential politics. During a party’s national convention, two men are the frontrunners to be their party’s nominee for president of the United States: William Russell, the cerebral, principled former secretary of state and Joseph Cantwell, a ruthless, unprincipled member of the U.S. Senate. Russell is politically virtuous but personally vice-ridden (he has a penchant for relations with women outside of his marriage), while Cantwell is abhorrent politically (in the McCarthy/Nixon vein) but personally virtuous. Vidal liked this balance of traits and used it to pitch-perfect precision in this play.

Vidal’s talents as a playwright came to their apogee with The Best Man (1960), a timeless classic on the machinations of presidential politics. Photo by the author.

Both men are vying for the endorsement of former President Art Hockstader, whose influence would sway the convention towards a candidate. When Hockstader decides not to endorse anyone, Cantwell threatens to make Russell’s infidelity public and Russell threatens Cantwell with disclosing an alleged homosexual relationship he had while in the Army. In the end, the rumors against Cantwell are unfounded, leaving Russell with no choice but to drop out. When Russell does, he shatters Cantwell’s chances by endorsing another man, John Merwin, ensuring him the nomination for the presidency.

I loved every second I spent reading this play. As a political junkie for most of my life, I adored the historical and political parallels Vidal wove throughout. In an age where so many politicians are corrupted both personally and politically, the moral ambiguities explored in this play are also more relevant than ever. Revivals of the play have continued periodically, and with the exception of some minor details, its events could have taken place today. The Best Man is an essential work from the canon of Gore Vidal, highlighting his strengths as a writer, dramatist, and political thinker.

After the success of The Best Man, Vidal adapted a play from the Swiss playwright Friedrich Duerrenmatt. Vidal was no stranger to adaptations, as some of his aforementioned plays for television were adapted from writers such as Henry James and William Faulkner. What attracted him to Duerrenmatt’s play becomes obvious once one starts to read it: it was a historical play based on the life of the Western Roman Empire’s final emperor, and the falling of said empire to the Goths. At the time, Vidal was finishing his first novel in years, the classic historical work Julian (1964), so he was already steeped in the Roman world, especially towards the end of its dominance.

Vidal’s version of Romulus is more of a farce than an historical play, which is in keeping with Duerrenmatt’s version, but it’s more punchy, funny, and politically astute. Romulus is a clod, obsessed more with his chickens than with statecraft; the Goths, by contrast, are portrayed more intelligently than one would have assumed. Vidal uses the play as a means to comment on the American political scene, as John F. Kennedy’s presidency was in full-swing, with its ascent of the spectacle over the substantive more pernicious with each passing day.

Unfortunately, the play never gained the success of The Best Man, and it would be one of Vidal’s final forays into theater, as his return to novel writing and his growing stature as an essayist became the focus of his career. Nevertheless, Romulus remains an interesting entry into his oeuvre, a historical play not fully grounded in historical fact but with incisive commentary on empires and their falls.

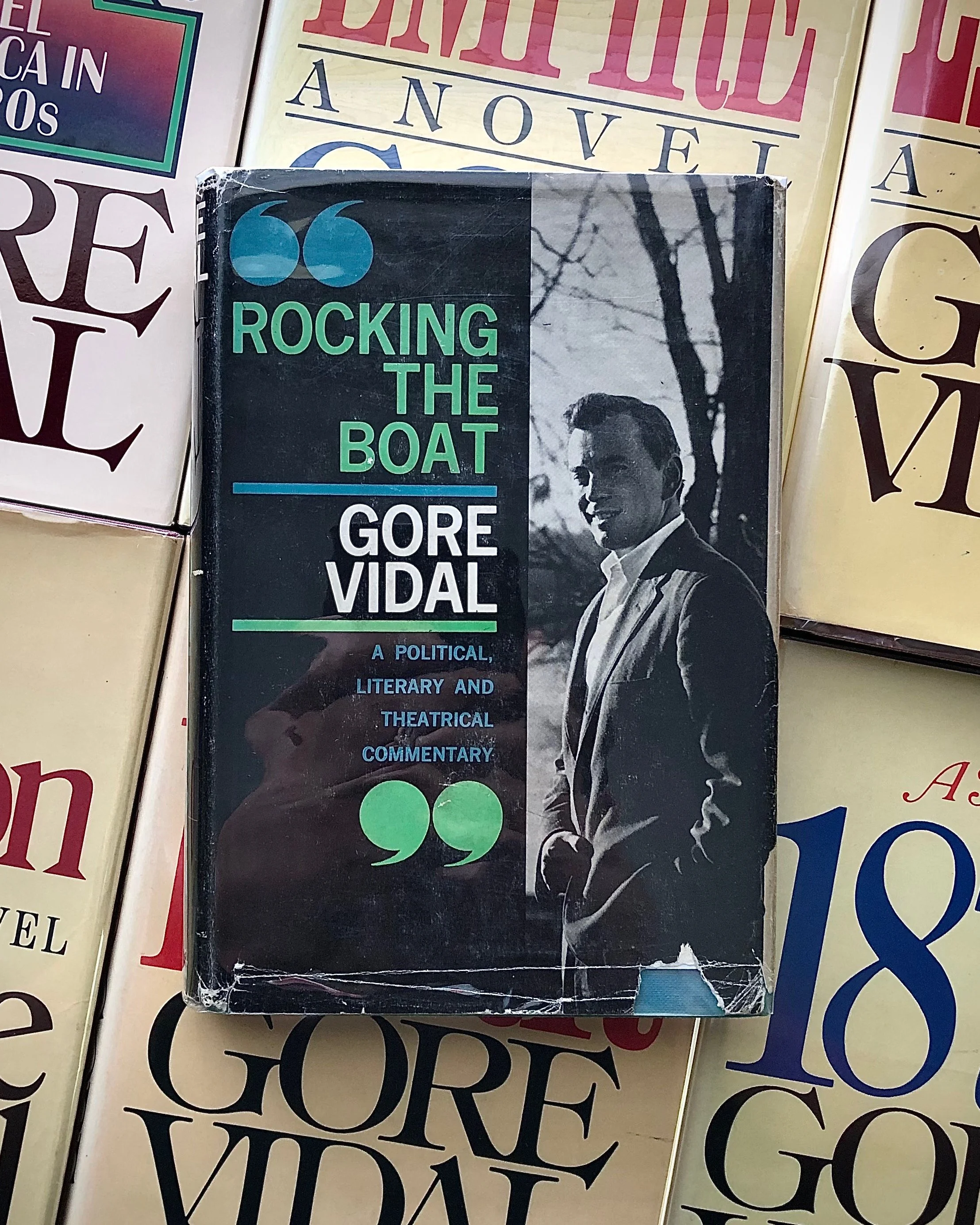

Alongside his talents as a playwright, Vidal became one of the premier essayists of his generation. In Rocking the Boat (1963), his first essay collection, he set his erudite mind on a wide array of topics related to politics, theater, and literature. Photo by the author.

Alongside his talents as a playwright, Vidal became one of the premier essayists of his generation. In Rocking the Boat (1963), his first essay collection, he set his erudite mind on a wide array of topics related to politics, theater, and literature. It’s exciting to read essays from his earliest years, comparing their conclusions to his later essays. You can get a sense of how he evolved as an essayist, inserting more of his acerbic wit as he grew more comfortable with the format.

One example of this evolution is the book’s opening essay, “John F. Kennedy: A Translation for the English,” which presents a rather straightforward analysis of the then-newly inaugurated commander-in-chief. Vidal ran for congress in 1960 and was a friend to JFK, which makes the tone of this piece more conciliatory than his later remarks on the age of “Camelot.” One striking phenomenon that Vidal points out is the growing ascendency of intellectuals in Kennedy’s orbit, a stark departure from the presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower. Vidal’s take-away is that Kennedy seems to be a genuine break with the past and how it’s all for the better. The Bay of Pigs debacle, which happened months after this piece was published and which Vidal comments on in the appendix, scuttled much of his optimism.

Many of the essays here are as timely as ever. “Closing the Civilization Gap” is a visceral reflection on the barbarism of police violence and the lengths to which society neglects to hold law enforcement accountable for its own crimes. “Love Love Love” comments on the growing trend in popular entertainment, in this case the theater, that abandons substantive emotional investigations in exchange for superficial sentimentality. He also writes passionately about the defense of civil liberties in two pieces focusing on the House Un-American Activities Committee and its retrograde investigations during the McCarthy era. My favorite essay is “Norman Mailer: The Angels are White,” an insightful meditation on the popular writer and the limitations of grasping for authenticity.

Rocking the Boat is a portrait of the essayist as a young man, still finding his voice and developing his talents as a commentator. It makes for fun, engaging, and always enlightening reading.

Return to the Novel and Other Pursuits (1964-1974)

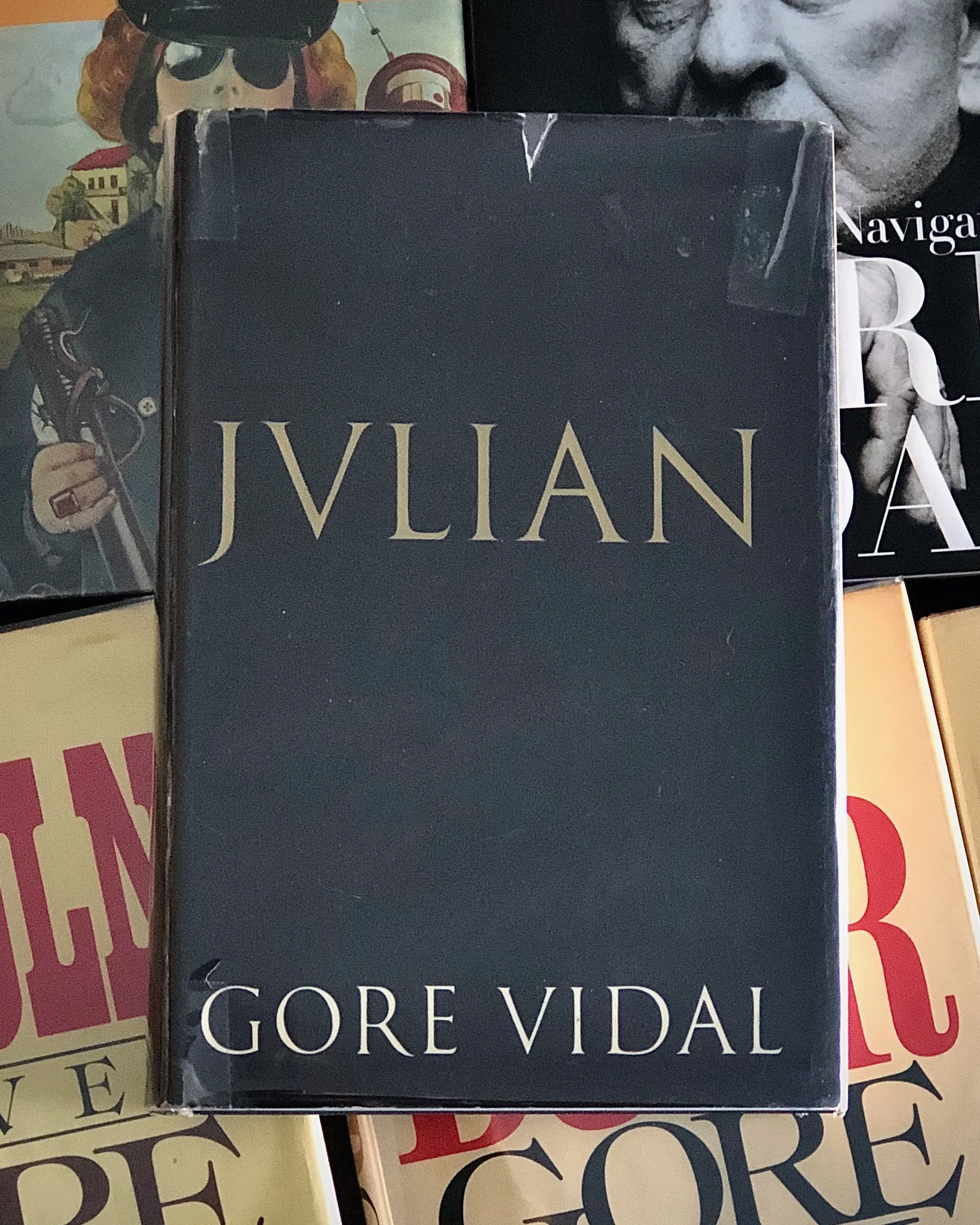

After a 10-year hiatus from the novel, Gore Vidal returned to form with Julian (1964), a classic of historical fiction and one of his greatest works. A lifelong skeptic and critic of organized religion, the backdrop of the 4th Century Roman Empire is a perfect place for Vidal to flesh out these ideas. Julian, Roman Emperor from 361 to 363 C. E., is our central character and the mouthpiece for Vidal’s trenchant critique of Christianity. As a relative of the emperor Constantine, whose conversion to Christianity changed the course of Western Civilization, Julian grew up surrounded by the ascendance of the new monotheistic religion. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Julian found no solace in the new religion, instead opting to study philosophy and ultimately pledging allegiance to the “old gods” of the Roman Empire. After the gruesome death of his brother, Julian becomes the Caesar of Gaul, securing the western lands for the empire through his brilliant military strategy. He plots an imperial coup against his cousin, Constantius, which proves to be pointless after Constantius dies naturally and Julian assumes the mantle of Roman Emperor.

After a 10-year hiatus from the novel, Gore Vidal returned to form with Julian (1964), a classic of historical fiction and one of his greatest works. Photo by the author.

Right away, he attempts to return Rome to paganism, providing for the free exercise of all religions while alienating and removing from power many allies of the empire who are “Galileans,” the term Julian uses for Christians. His main critique of the new religion is that it is a religion of death, whose worship of a dead man signals its clear departure from the “true gods” of antiquity. His plans for shaping the ideological future of Rome are put on hold when he must fight the Persians to the east. Despite winning many battles, the ravages of war leave Julian and his army ill-equipped for the conquest of the east, and Julian himself dies in battle.

The novel is formatted in an epistolary way, as a series of letters between Priscus and Libanius, two colleagues of Julian, alongside the memoirs and journals of the emperor himself. It provides the reader with multiple perspectives on the same events, showing how history is shaped by those who write it. Julian showcases Vidal as a master storyteller; he weaves a tale epic in scope and philosophical in tone that ranks highly among other greats of historical fiction.

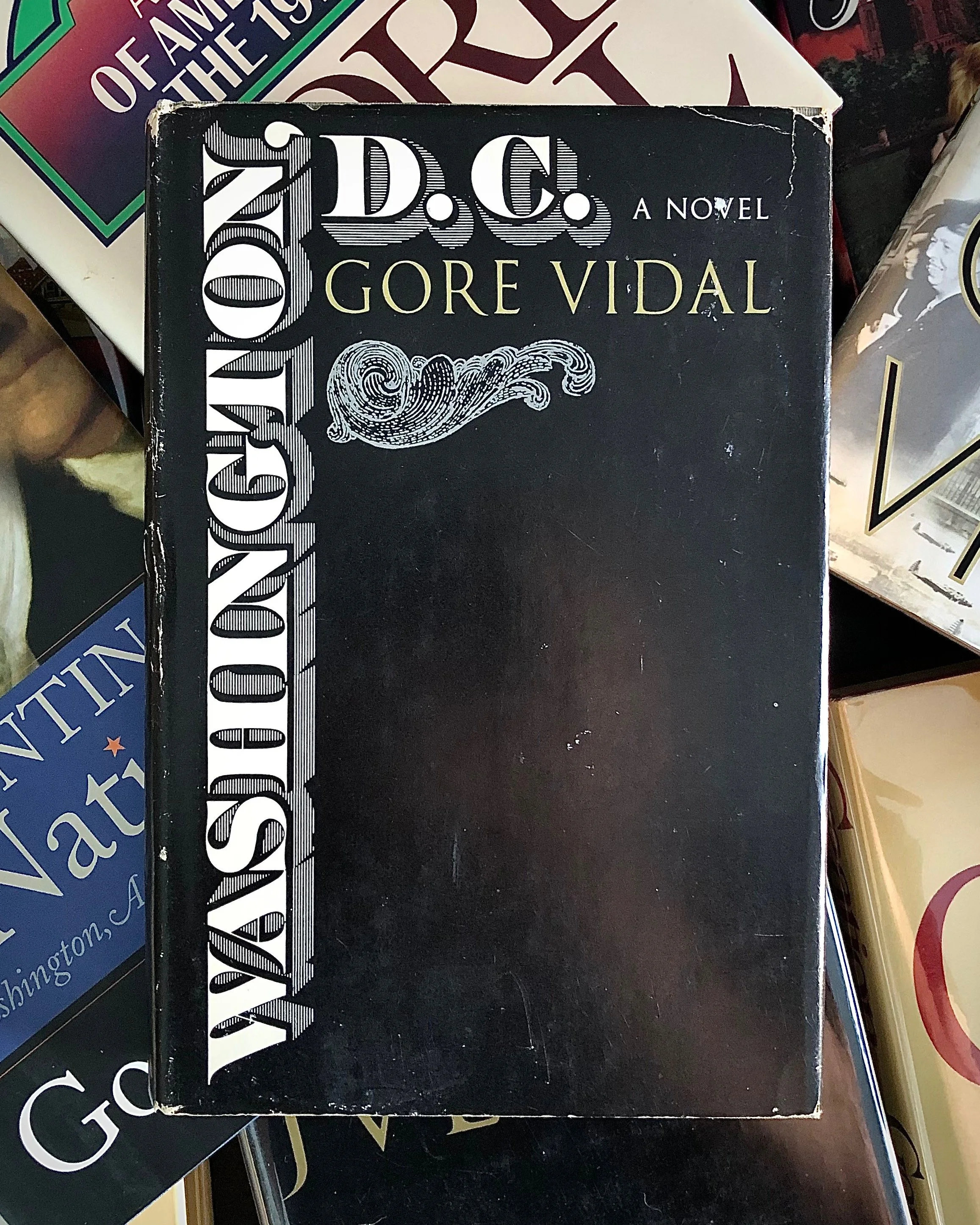

After the critical and commercial success of Julian, Vidal published Washington, D.C. in 1967. The first book in his “Narratives of Empire” series, it showcased his unique and challenging perspective on the history of the United States from the late 1930s to the mid-1950s. While it is a novel with a large cast of characters, it mostly follows three main figures: Senator James Burden Day, Senator Clay Overbury, and journalist Peter Sanford. Day is a Senator from old Washington, whose battle for power puts him in the crosshairs of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the New Dealers. His staunch isolationism and populist appeal is likely inspired by Vidal’s own grandfather, Thomas Pryor “T.P.” Gore. Overbury is originally Day’s assistant who marries a socialite daughter of a powerful newspaper magnate that hastens his rise to power. A veteran of World War II, Overbury’s heroic actions during the war (which are later disputed) see him elected to the House and then the Senate. Clearly this character is inspired by John F. Kennedy, who Vidal had a brief friendship with and who supported the author’s run for congress in 1960. Finally, there’s Peter Sanford, the son of the aforementioned publisher whose journalism challenges Overbury, McCarthyism, and the darker aspects of Washington. This character is the closest to Vidal himself.

The first book in Vidal’s “Narratives of Empire” series, Washington, D.C. (1967) showcased his unique and challenging perspective on the history of the United States from the late 1930s to the mid-1950s. Photo by the author.

The novel is breathtaking in scope and rich in historical allusion, with numerous references to FDR, Truman, Eisenhower, and many other major and minor figures of American history. Vidal is masterful in his prose, giving readers compelling dialogue, complex characters, and a backdrop of power that eventually corrupts the once incorruptible. His major theme, which connects much of his writing, is the decline of the American Republic and the rise of the American Empire, with all the complications that accompany it: the loss of innocence, the elevation of the trivial, and the subordination of society to militarism. All these ideas permeate Washington, D.C., one of the essential works from Vidal’s historical novels.

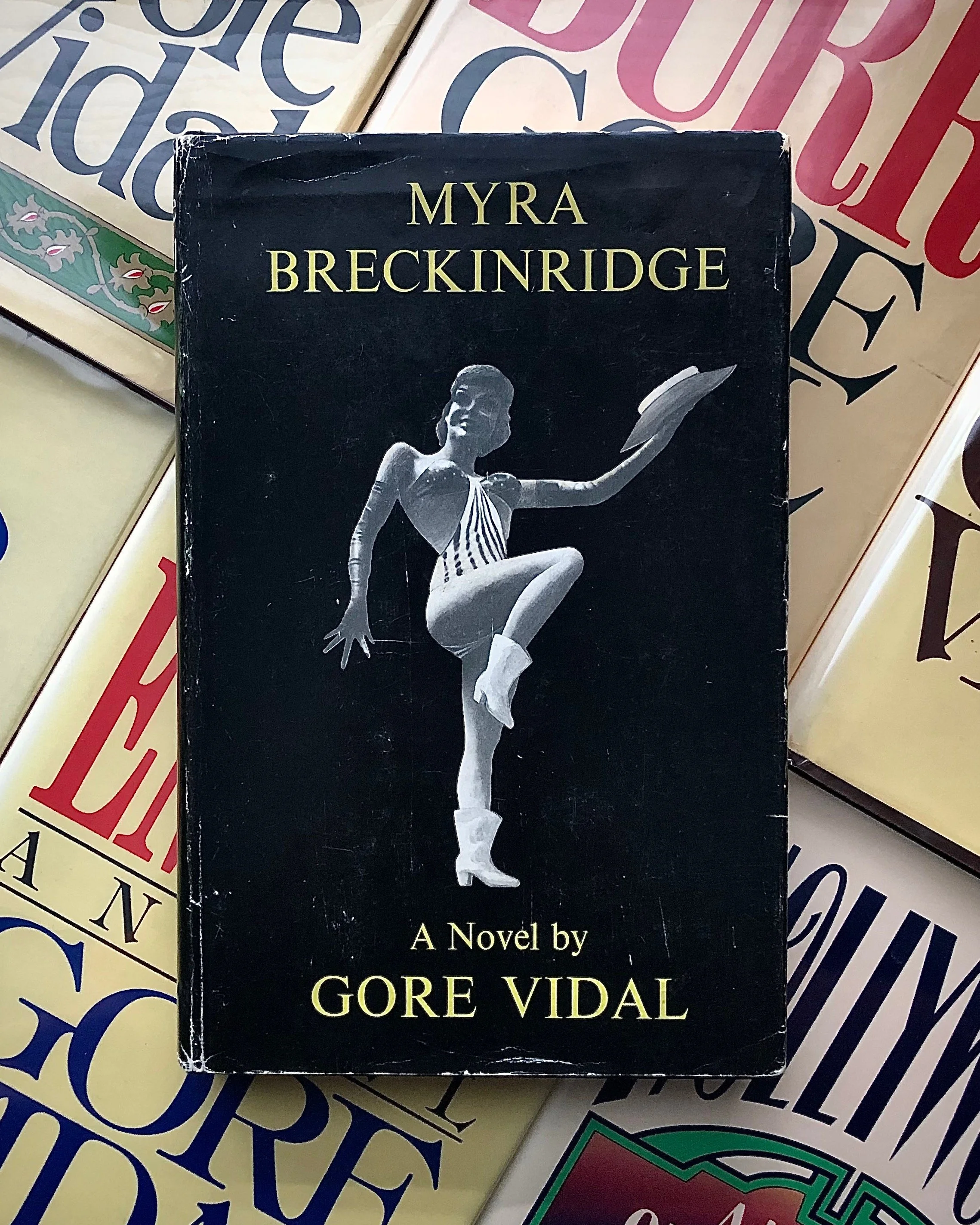

There’s no question that Gore Vidal’s most iconic and controversial novel from the 1960s is his gender-bending farce, Myra Breckinridge (1968). The title character is a devilishly witty trans woman obsessed with the “Golden Age of Cinema,” which in her eyes is 1935-1945. Throughout the novel, which is largely written as a series of journal entries, Myra name drops classic films and film stars as ways to describe her beauty, grace, or genius. She lands in California at the doorstep of her uncle-in-law, the western film star Buck Loner, who runs a drama school. She has come to collect her share of what was bequeathed to her deceased husband Myron. In the meantime, she becomes an instructor at Buck’s school, teaching classes on “posture” and “empathy.” This setup gets to the heart of the novel, which is that Myron is actually Myra, a trans woman dedicated to the destruction of the all-American male and traditional sex roles. She fulfills her goals through sabotaging a relationship between two young students, Rusty and Mary Ann, emasculating the former and enchanting the latter. Myra eventually becomes Myron again, marrying Mary Ann and living a quiet life in the suburbs, or so we think.

There’s no question that Gore Vidal’s most iconic and controversial novel from the 1960s is his gender-bending farce, Myra Breckinridge (1968). Photo by the author.

Myron (1974), Vidal’s sequel to Myra Breckinridge, is an entertaining romp in its own right. Vidal leans hard into speculative fiction territory, transporting Myron into the summer of 1948 via a late night showing of a film on television. Being abruptly transported into the production of the film, called Siren of Babylon, Myron’s other personality of Myra continues to push through his consciousness. Vidal deftly alternates the narrative voice between Myron and Myra, showing the conflict between the two voices within one person. In the end, it is Myra who wins out in the melee, living out her silver screen fantasies by transporting into the body of the female lead of Siren of Babylon, Maria Montez. She then comes back to her (or his) own body and cements her, or his, destiny—sort of. While Myra Breckinridge is the better novel, I very much enjoyed reading Myron and loved all of its science fiction elements. Taken together, both novels are Gore at his most outlandish, vulgar, and beautifully tacky.

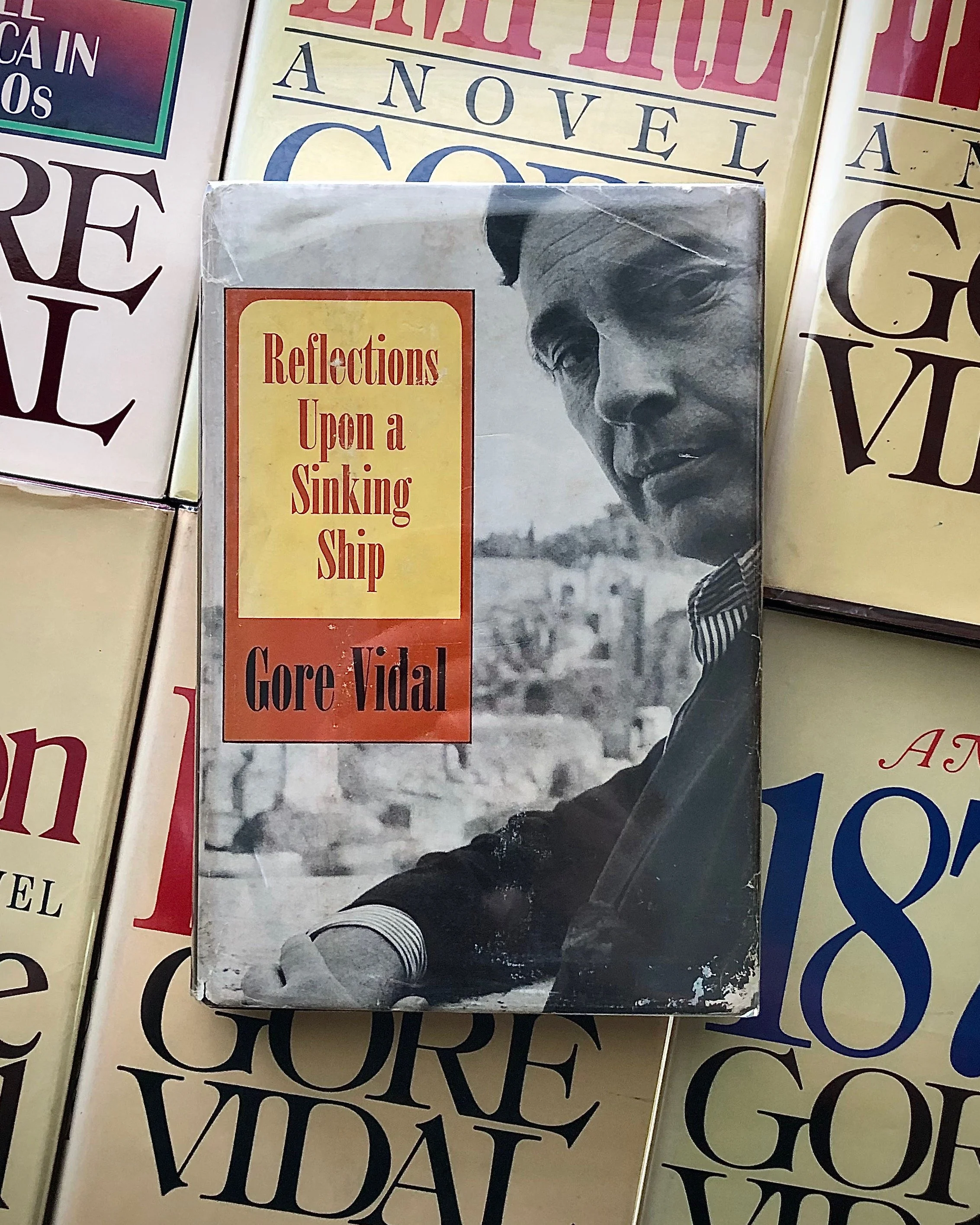

By the late 1960s, Gore Vidal was a household name, with the publication of his controversial, bestselling novel, Myra Breckinridge, as well as his intellectual sparring match with William F. Buckley during the 1968 party conventions. He had also developed into one of the country’s premier essayists, publishing in Esquire, the New York Review of Books, and occasionally in the New York Times.

Reflections Upon a Sinking Ship (1969), his second essay collection, displays the wide-ranging subjects Vidal would take on during this period, from the development of the French “New Novel,” to the enduring mythology of the Kennedy family. I particularly liked his essays related to sexuality, as Vidal defiantly defends freedom of expression and provides an exegesis on the erotic fiction of Henry Miller. In the same vein, Vidal explicates his own revisions to his path-breaking 1948 novel, The City and the Pillar, reflecting the changing sexual mores of the 1960s.

Reflections Upon a Sinking Ship (1969), Vidal’s second essay collection, displays the wide-ranging subjects he would take on during this period, from the development of the French “New Novel,” to the enduring mythology of the Kennedy family. Photo by the author.

Another excellent essay from the collection is “Edmund Wilson, Tax Dodger,” a review of the legendary critic’s book, The Cold War and the Income Tax. Wilson, whose opaque finances required a closer look by the IRS, used his experiences to share how the growth of the National Security State bilked the American public out of billions while leaving them no safer from threats abroad. Here Vidal is using the example of Wilson as a means to share his own misgivings on the rise of the American Empire.

Without a doubt, the best essay in the collection is “The Holy Family,” Vidal’s long diatribe against the myth-making around John F. Kennedy, especially in relation to the publication of memoirs from multiple Kennedy aides and friends. You get from Vidal an honest rendering of the man: a charming, if ineffectual president bogged down by an equally ineffective Congress and multiple foreign policy blunders. Additionally, Vidal wrote an essay on William Manchester’s era-defining book, The Death of a President. Jackie Kennedy explicitly forbade Manchester from publishing certain sections of the text, making the finished product an insufficient analysis (another example of why people continue to proffer JFK conspiracy theories). These essays are prime Vidal, and I would recommend this collection to anyone starting to delve into his extensive body of work.

For many years, Gore Vidal maintained that he would never write a memoir. Of course, this would change with the publication of his two memoirs, Palimpsest (1995) and Point to Point Navigation (2006). But before that happened, the closest one would get to a memoir from Vidal was through his novels. With works such as The Season of Comfort (1949), The City and the Pillar (1948), and Washington, D.C. (1967), you would get glimpses of his life, from his upbringing in the nation’s capital with a famous senator grandfather to the complicated relationship he had with his mother.

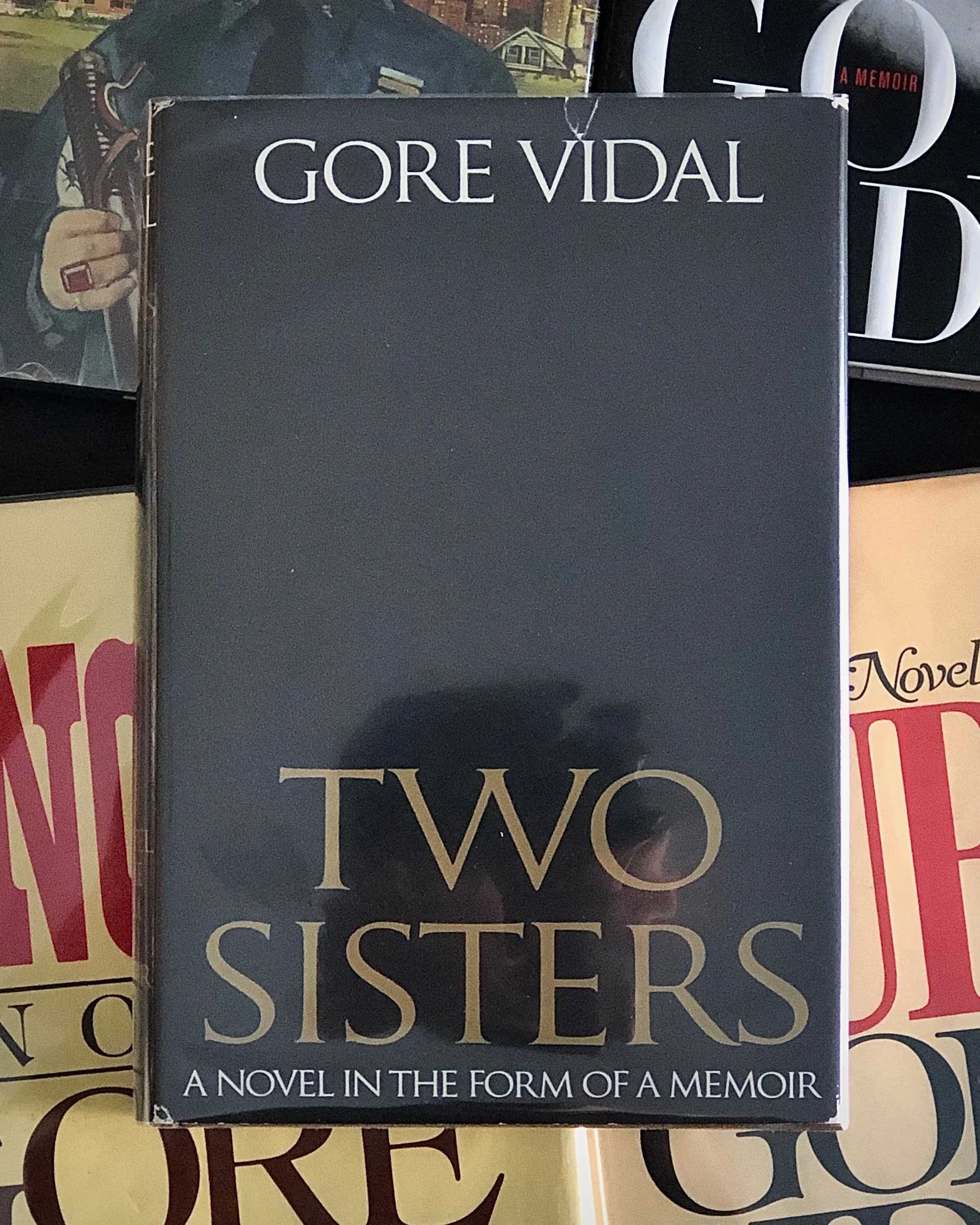

Subtitled “A Novel in the Form of a Memoir,” Two Sisters (1970) follows Gore Vidal as he uncovers a long-lost manuscript from a friend, who was charged with writing a screenplay of a sword-and-sandal epic during the Golden Age of Hollywood.

This is what makes Two Sisters (1970) such an interesting entry into his body of work. Subtitled “A Novel in the Form of a Memoir,” Two Sisters follows Gore Vidal as he uncovers a long-lost manuscript from a friend, who was charged with writing a screenplay of a sword-and-sandal epic during the Golden Age of Hollywood. What his friend left behind was nowhere near that simple, as his screenplay (which readers get to experience through a third of the novel) is more of a character study of two sisters whose loyalties and familial ties ultimately rip their lives apart. The shocking revelation in the screenplay is that one sister is with child by her brother, which reflects the “real life” story within the novel that the screenwriter also had a child with his sister, which for years Vidal thought was his own.

The lines between fact and fiction are often blurred in the novel, with Vidal recounting real-life stories intermixed with invented characters and scenarios. Two Sisters, while considered a lesser work, is Vidal at his postmodern best, challenging the reader to wade through multiple perspectives, half-truths, and complete fantasies. I found it a quick, enjoyable read that underscores Vidal’s talent for shifting the narrator and mixing literary styles so seamlessly that the reader can’t help but turn every page. It may not be one of his essential works, but it is nonetheless one of his most creative and challenging.

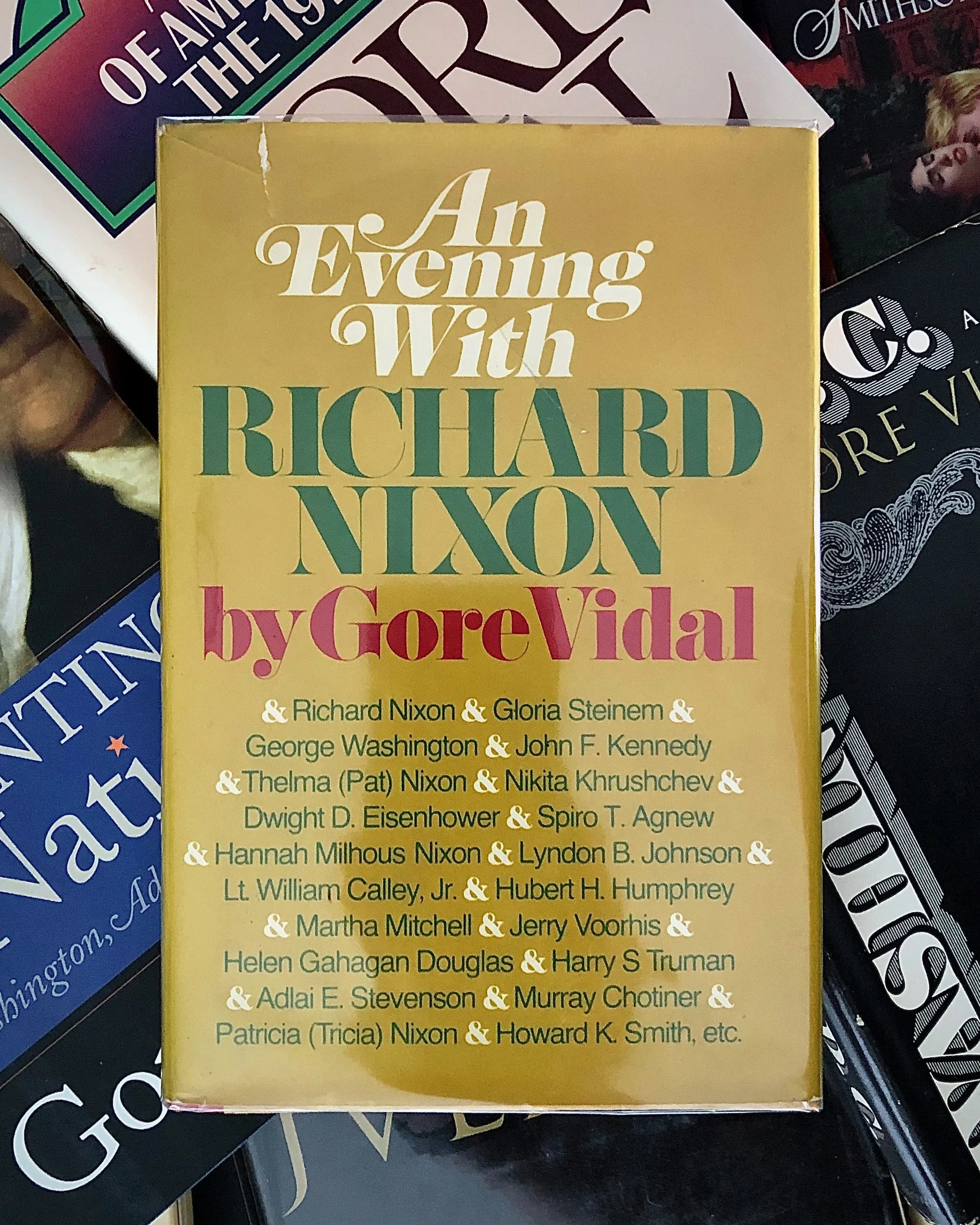

In 1972, Vidal returned to the theatre for a topical and irreverent take on the country's then-current Commander-in-Chief. Richard Milhous Nixon, the 37th President of the United States, is one of history’s most complex and morally challenging characters. The only president to resign from office due to the imbroglio of Watergate, Nixon remains an enigma for historians and the general public. In 1972, at the height of Nixon’s power, Gore Vidal attempted to provide said public with an entertaining and enlightening look at “Tricky Dick” with his play, An Evening With Richard Nixon. Equal parts satire, biography, political analysis, and history, the play has the character of Nixon speak with only his own words, as documented in newspapers, books, and television appearances. George Washington, the narrator of the play who appears like an American history version of the Ghost of Christmas Past, displays to the audience Nixon’s political shrewdness, arrogance, and hubris through cutting monologues.

In 1972, at the height of President Richard M. Nixon’s power, Gore Vidal attempted to provide said public with an entertaining and enlightening look at “Tricky Dick” with his play, An Evening With Richard Nixon.

We learn of Nixon’s humble beginnings in California, his family’s struggle to make ends meet, his inability to grasp the brass ring of a Harvard Education, his (rather meager) wartime service, his red-baiting years in Congress and the Vice-Presidency, and finally, the oval office, as the paranoiac-in-chief. Written in a fabulous but nevertheless learned style, An Evening with Richard Nixon is Gore Vidal playing to his strengths as a political commentator, historian, and social critic. If a person knew nothing about Richard Nixon, this play would be a good primer on his life and work. Of course, Watergate, the resignation, and the years in the wilderness during the post-Presidency are not covered, but the play gets to the heart of Nixon as a political animal. He elevated lying and character assassination almost to an art form, always believing that the ends justified the means. This play describes for viewers or readers the fallout from all that dross, and for that, it is a worthy read from the works of Gore Vidal.